Birthday surprise for WWII pilot reunited with pieces of his past

When Capt. Alan Carlton’s B-24 bomber was shot down over Germany during World War II, he felt lucky.

Not that lucky — wounded in the right foot, he left a bloody trail in the snow that made him easy to track. The American pilot was captured at gunpoint and spent more than a year in a POW camp.

But he was alive, which was more than could be said for three of his crewmen.

Now, 75 years later, Carlton has another reason to feel lucky about what happened that day. It came via FedEx a few days ago from Eisenach, a city in central Germany.

Eberhard Haelbig, a researcher there who is documenting aerial combat during the war, scours crash sites found near his home. Dozens of planes went down there. Scavenged over the years by humans, consumed by the elements, what’s left is mostly pieces.

But even they tell a story.

One plane in particular, a B-24 that crashed in a forest, caught his attention not long ago. Using records in Germany and the U.S., he figured out which plane it was, and when it had gone down.

He learned the names of the 10 Americans who were on board, and found photographs taken shortly after it crashed. With the help of Google and a military friend in the states, he contacted the pilot, who lives in a senior community in Carmel Valley.

Which is how Carlton got two FedEx boxes with remnants of his B-24.

“With this I would like to say, ‘Thank you, Capt. Carlton,’ and thank you to the Greatest Generation for your fight against evil and for liberating my country from that,” Haelbig said in an email interview with the Union-Tribune. “I’m a German by birth, but American by heart.”

What he sent Carlton is a pile of junk to a layman’s eye. But not to the former pilot.

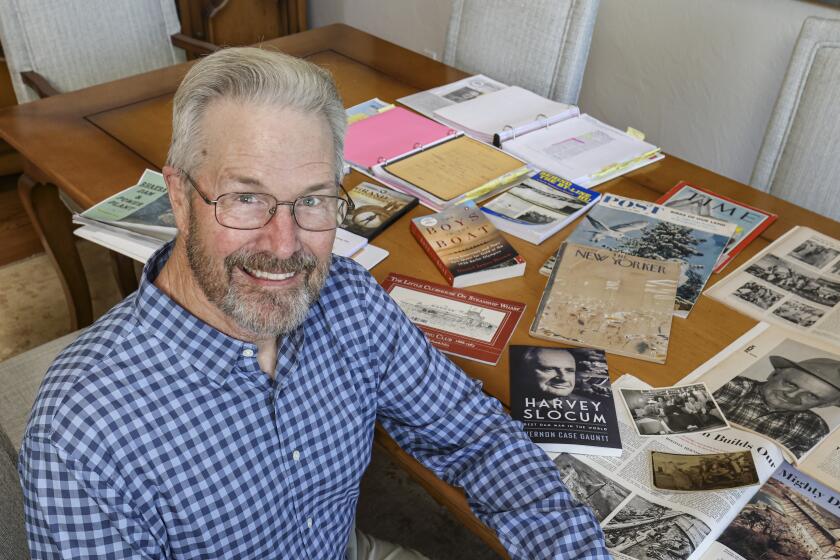

“This means a lot to me,” Carlton said Thursday morning as he looked through the seven pieces of metal and glass. He held up a scrap he thinks was the part of a wing tip called an aileron. “I never thought I’d see any of my plane again. I’m glad to have these.”

Glad, too, because the package arrived in time for his 100th birthday, which was Sunday. “What a nice, early present this is,” he said.

His 14th mission

They called it Big Week.

As 1943 turned into 1944, Allied commanders hatched a plan for a round-the-clock aerial offensive against the Nazis, one of the largest bombing campaigns of the war.

American B-17s and B-24s stationed in England and Italy would attack airplane factories, munitions centers and other targets in Germany during the day. British planes would raid at night.

They hoped not only to strike at Germany’s industrial heart, but draw its fighter jets into a war of attrition and clear the skies in advance of the pivotal D-Day land invasion at Normandy planned for later that year.

For six days starting on Feb. 20, 1944, hundreds of B-17s and B-24s flew missions into Germany, dropping nearly 10,000 tons of bombs.

They paid a hefty price, losing about 250 bombers and fighters. Some 2,500 crew members were killed, injured, lost or captured.

But Germany lost hundreds of planes and pilots, too, and with its factories and airfields damaged by the bombs, couldn’t replace them quickly.

The Allieds had shifted air supremacy in their favor.

Carlton was shot down during Big Week, on Feb. 24, 1944. The Detroit native had enlisted two years earlier, dropping out of medical school at Indiana University “to do my part in the war effort,” he said. “Everybody was joining.”

Part of the 567th Bomb Squadron based in Hethel, England, Carlton was on his 14th mission when his B-24 D Liberator, built at Consolidated in San Diego, was hit by enemy fire, first over Holland, and then over central Germany.

Machine-gun bursts from Luftwaffe fighter planes killed his tail gunner and two waist gunners, and sent the B-24 rolling. Everybody else parachuted out the bomb bay doors, with Carlton exiting last.

His came down between two trees, suspended in the air. After cutting himself free, he hobbled away, but his right foot — wounded by shrapnel when the plane got shot — trailed blood in the snow. German civilians hunted him down about two hours later and held him at gunpoint until the military arrived.

From there he was interrogated briefly, then put on a train and sent to Stalag Luft I, a prison camp for Allied air crews located near Barth, Germany, on the Baltic Sea. Nearly 9,000 British and American aviators were captive there.

A journal Carlton kept during his imprisonment includes drawings he made of the camp, as well as a map of his ill-fated mission. It has lists of books he read and movies he saw, and recipes the prisoners used for meals made from care-package ingredients like Spam. And meals made from animals.

“Whatever we could catch, we ate,” Carlton said. When Russian forces liberated the camp in early May 1945, his weight had dropped to about 100 pounds.

B-17s and B-24s arrived to pick up the prisoners. On the way out, they flew their passengers over German cities so they could view the results of the bombings they’d participated in before getting shot down.

“I was happy to see it,” Carlton said.

An unusual ending

Haelbig, the German researcher, works for a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the story of one particular World War II aerial battle: The Kassel Mission.

On Sept. 27, 1944, B-24s from the 445th Bomb Group, stationed at Tibenham in England, were sent to hit factories in Kassel. A group of about 35 planes, through what the American Air Museum in Britain called “a gross error in leadership and navigation,” peeled off from the main group and their fighter escorts to attack a different town.

The bombers were overrun by about 150 German fighter planes, which in six minutes shot down 25 of the B-24s. Six others made emergency landings in Allied territory. Only four made it back to Tibenham.

It was, according to the Kassel Mission Historical Society, “the greatest single-day loss to a group from one airfield in aviation warfare history.” More than two-thirds of the crew members were killed or taken prisoner.

While his main focus is documenting the stories of the Kassel Mission, Haelbig is also interested in other aerial warfare in the region, including Big Week. He said almost 30 U.S. planes were shot down in just one day during that campaign near Eisenach, his hometown.

Hunters and rangers in the nearby forest sometimes come across the wreckage of planes, and when they do they tell Haelbig. He visits the sites and collects what he can, often putting the remnants in display cases in an aviation museum.

He identifies the planes and their crew members through detailed records, maps and photos kept in U.S. and German archives. That’s how he linked Carlton to that particular B-24.

The search usually ends there. Of the 16 million Americans who fought in World War II, fewer than 500,000 are alive, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

But when Haelbig Googled Carlton’s name recently, he found a 2016 newspaper story about the pilot that said he was living in San Diego. The researcher asked an American friend on the East Coast to find out if that was still true.

“It was my greatest wish to send Capt. Carlton the pictures of his plane and some pieces,” Haelbig said.

When the phone call came, Carlton and his daughter, Jan Foreman, didn’t know what to make of it. Someone found the B-24? They want to send parts of the wreckage?

“We thought it was probably a scam,” Foreman said.

Reminders of what happened

Carlton’s memory about the war isn’t what it used to be.

“That was a long time ago,” he said.

He came home from Germany and into the arms of his wife, Jeanne. They started a family, two daughters. They followed his parents from Chicago to Arizona and then to San Diego, where he sold real estate for many years in Rancho Bernardo. His grandsons are in the Grammy-winning Christian group Switchfoot.

He and Jeanne were married for almost 75 years until she died in 2016. His senior-living apartment is filled with photos of the couple, including a black-and-white one where he’s in his military uniform, before he was shipped overseas.

To remind him of what happened during the war, he has scrapbooks and a shadow box decorated with medals — a Purple Heart, two Air Medals, the French Legion of Honor. The pieces Haelbig just sent him from the downed B-24 may play a similar role.

And he has a poem he wrote while he was a POW that includes near the end this stanza, as true now as it was then:

It’s a hell of a life and you feel the strain

But you’d do the same thing all over again.

Still you pray for the day when there’ll be no more war

When you’ll see what it is you’ve been fighting for.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.